The natural reservoir of Ebola virus (EBV) remains unknown, although scientists presume that bats are an essential feature of its virus cycle and transmission to humans. Committed to improving knowledge of EBV ecology and epidemiology, the EBO-SURSY Project partner, Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement (CIRAD), has built an online data portal which tracks the sampling of bats, and maps the roll-out of critically needed capacity building trainings for veterinarians and other professionals involved in epidemiological surveillance in project countries. The data collected could shed light on which bat species (likely to be multiple) are a part of the EBV reservoir and when virus spillovers could occur, as well as which organisations would have the capacity to respond to such a health emergency in West and Central Africa.

Figure 1: A fruit bat (Eidolon helvum) is captured by the CIRAD team for sampling and tagging. This collar will allow scientists to track the bat’s migration in West and Central Africa. Photo: ©CIRAD/ J.Cappelle

Many bats are migratory, some of whom may travel over a thousand miles in search of food and mates. They are easily adaptable to seasonal changes and resilient to food scarcity, which has ensured their survival on six continents. Tireless promoters of biodiversity, they act as pollinators, pest control and seed dispersers, all vital occupations within a healthy ecosystem. However, due to their long migrations, they also may contribute to the propagation of potentially zoonotic pathogens which they carry, such as the rabies virus, EBV, and certain coronaviruses, over vast territories.

While the bats are often asymptomatic to these viruses they host, when transmitted, they harm or be fatal to other animal and human populations. As long as the species of bat which hosts EBV remains unknown, it is not possible to accurately determine the conditions of how or if bats transmit EBV directly to humans or through an intermediary. This makes surveillance and research on the dynamics of viral spread even more important for the early detection and control of future outbreaks.

To better understand how bats are interacting on an environmental level, EBO-SURSY Project partners CIRAD, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD) and Institut Pasteur, share a common data portal which maps where humans, domesticated animals and bats have been sampled for EBV, other haemorrhagic fever viruses, and coronavirusesThe sampling of humans and domesticated animals will help the project better understand the dynamics of interspecies transmission and risk of spillover from wildlife. Additionally, because the reservoir for EBV is suspected to be maintained through a community of different fruit bat species, the partners provide detailed information on their sampling, including a visual estimation of species type, the location found, and multiple biological samples (blood, faeces, saliva). All this data is collected and uploaded to the online scientific portal to encourage information sharing between EBO-SURSY Project partners, as well as with other projects who are similarly battling against the emergence of another Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak.

Figure 2: The CIRAD team attaches a geolocation collar to a anesthetized fruit bat, while taking precautions to not come into direct contact with the bat or its bodily fluid. Photo: ©CIRAD/ J.Cappelle

The capture and sampling of bats is not an easy task, however it can be an excellent opportunity to further understand the role of suspected hosts in the circulation of EBV by employing the use of geolocation tracking collars. CIRAD researchers in the Republic of Guinea dedicated three nights to the capture of 5 male bats heavy enough to support the weight of a geolocation collar. Specifically, 5 urban-dwelling bats of the straw-colored (Eidolon helvum) fruit bat species, which have been shown to harbour EBV antibodies. When the bats were caught, they were anesthetised to prevent causing unnecessary stress, their biometrics were taken, and the collars were fitted. The bats were then placed in cages to recover, free to wake up and fly off into the night.

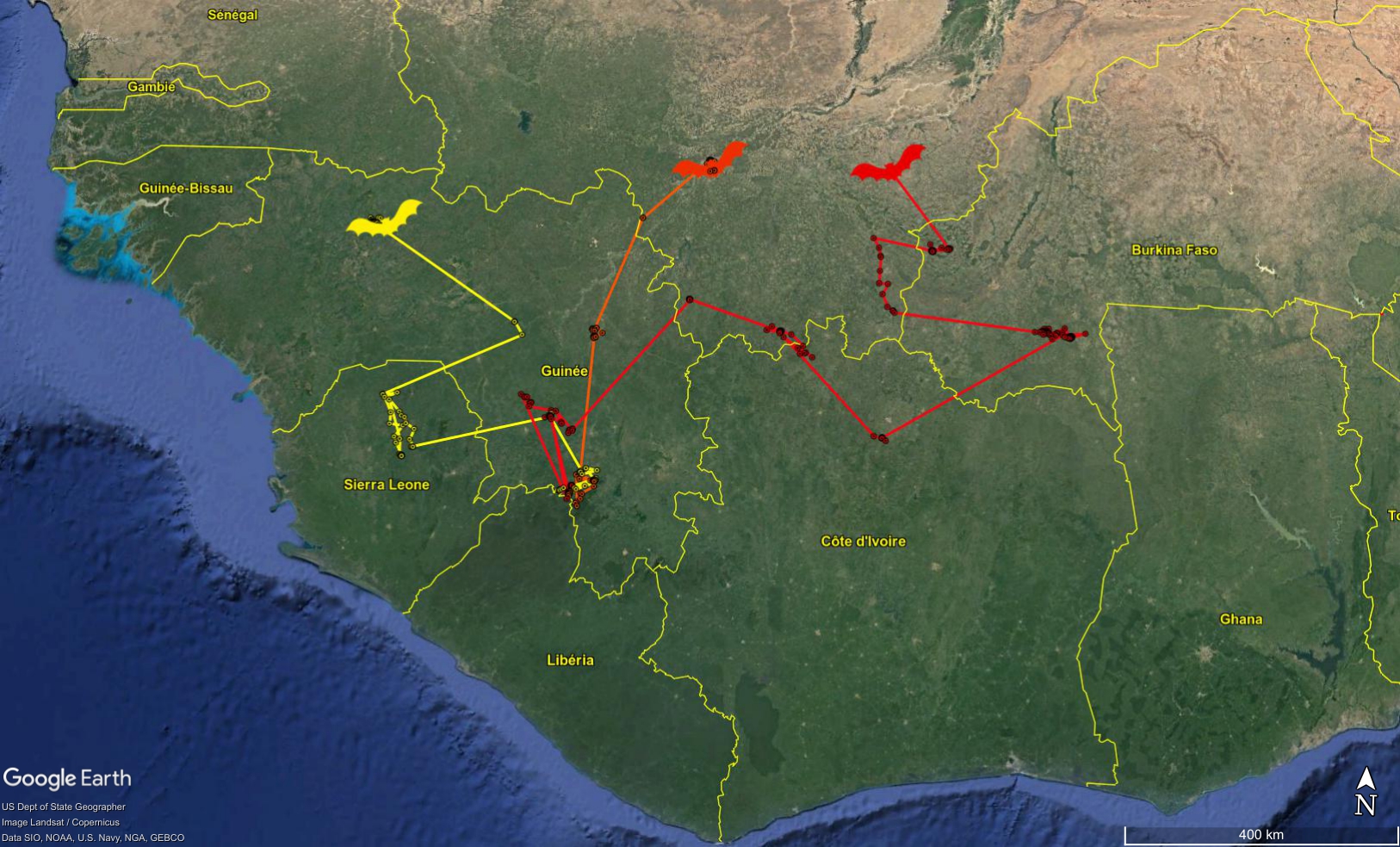

Using the satellite data from the collars, CIRAD has produced a geolocation map which tracks the migration of tagged bats, demonstrating their mobility and potential at spreading zoonotic pathogens. While three of the bats have currently migrated towards Mali or its border, their individual routes diverged greatly, revealing a bat’s natural appetite for travel and finding delicious fruit. One bat spent a short holiday in Sierra Leone before traveling to northern Guinea. Another left the southern Guinea sampling site to visit southern Mali, then quickly took flight for Liberia and the Hauts-Bassins of Burkina Faso, before turning again towards Mali. Yet another, enjoyed the sweetness of Kankan mangos in Guinea before swooping by the OIE local Bamako office 600km away, settling into a mango groove just outside.

Figure 3 This geolocation map partially details the flights of three bats which had been tagged by CIRAD in March 2020. Photo: ©CIRAD/ J.Cappelle

It seems therefore that the migration period has officially begun, and fruit bats are in full circulation in West and Central Africa. These three bats have already crossed country borders nine times since they were caught by the research team in southern Guinea, and their journeys show no sign of slowing down. Their non-linear movements and ability to transmit pathogens across a large territory further underscore the need to build regional epidemiological surveillance capacities. Accordingly, while the bats continue their search for fruit, the EBO-SURSY Project will continue their search for the EBV reservoir and strengthen virus surveillance to improve early detection for the next EVD outbreak in West and Central Africa.

Access our capacity building data map to know more about EBO-SURSY trainings, or access the scientific data map to track the project’s sampling activities! To learn more about the project, please visit our website.

READ MORE: visit the EBO-SURSY Project website

[1] With the financial support of the European Union, the OIE-led EBO-SURSY project implemented in coordination with CIRAD, IRD and the Institut Pasteur, aims to reinforce the capacity of national Veterinary Services in ten West and Central African countries to monitor and respond to the Ebola virus as well as four other haemorrhagic fevers – Marburg virus disease, Rift Valley Fever, Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, and Lassa fever. These five illnesses are zoonoses or diseases that can spread from animals to humans.

Banner Map: ©CIRAD/ J.Cappelle